Intro

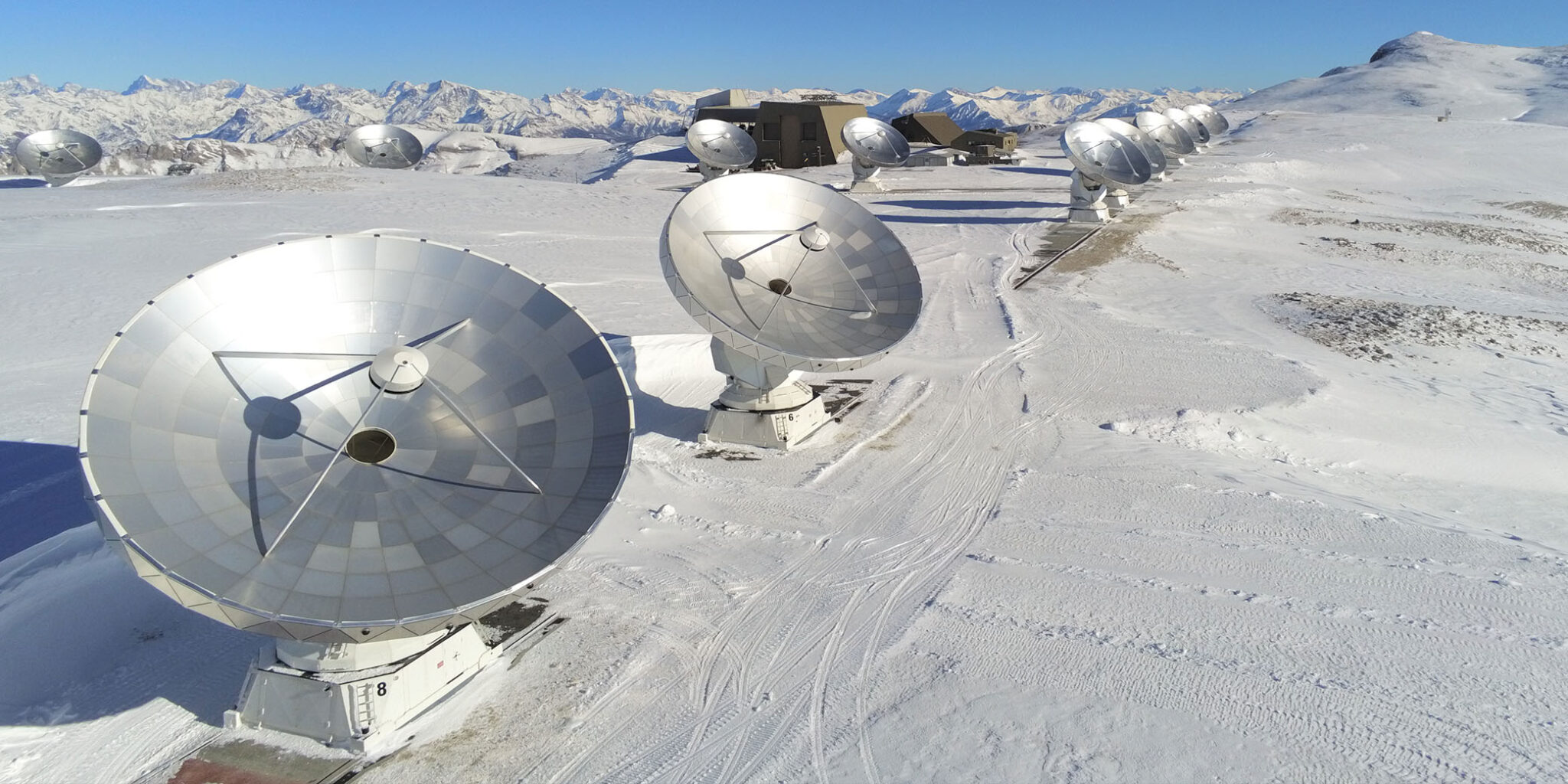

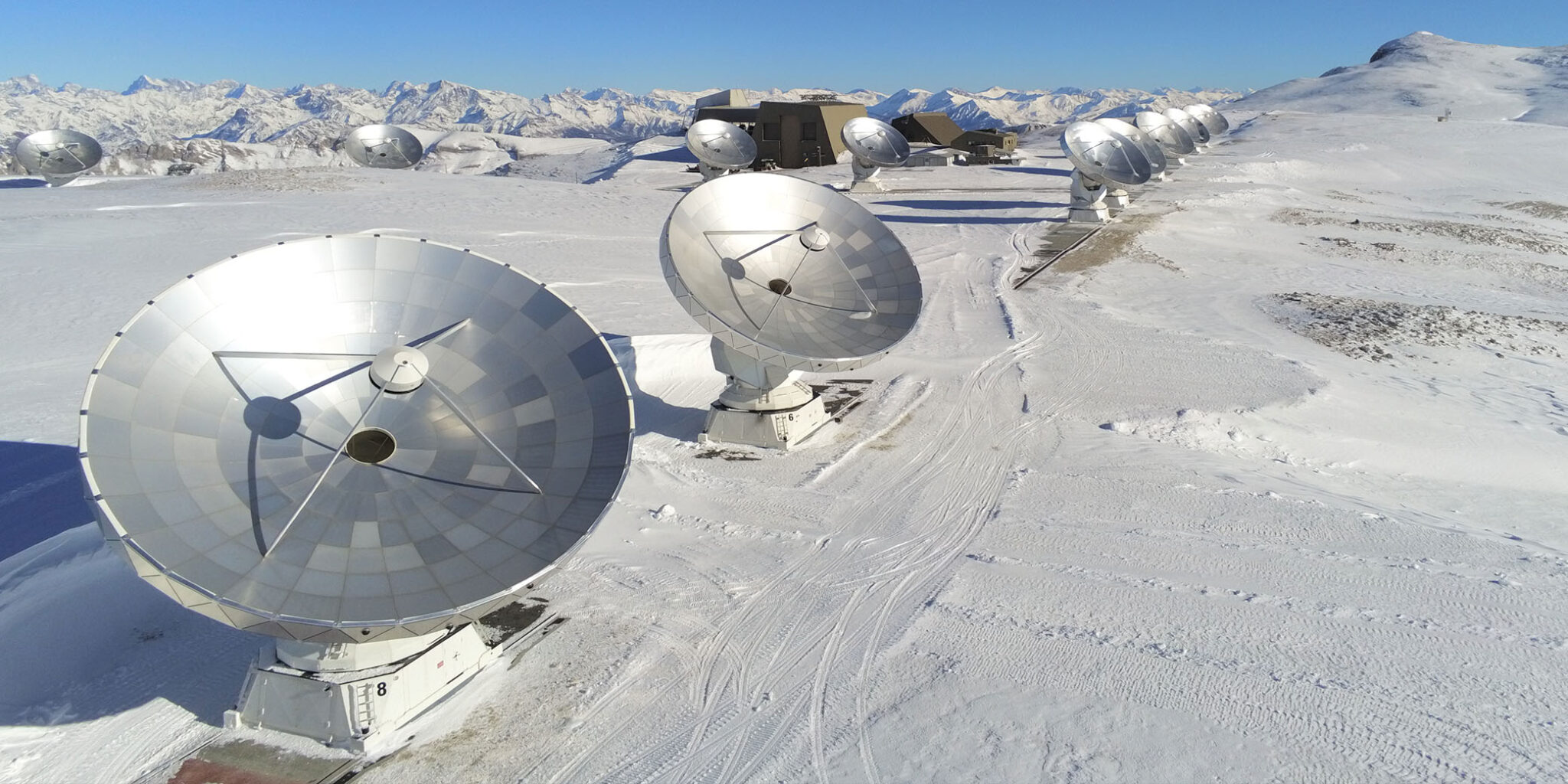

I am a Research Fellow at the University of Leeds' School of Physics and Astronomy. In my research, I focus on the formation of stars out of clouds of gas and dust, mostly in our own galaxy, the Milky Way. To do this, I make use of data coming from telescopes that operate from infrared to radio wavelengths, such as the wonderful Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique (IRAM) 30-m telescope in southern Spain (pictured), and the 15-m James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii.

If you want to find out more, visit my research page.

Research

This page contains a selected overview of some of the projects that I am most closely involved in. My full publication list can be found on the ADS, ORCID, or Google Scholar. My GitHub page can be found here.

GASTON: (Galactic Star Formation with NIKA2)

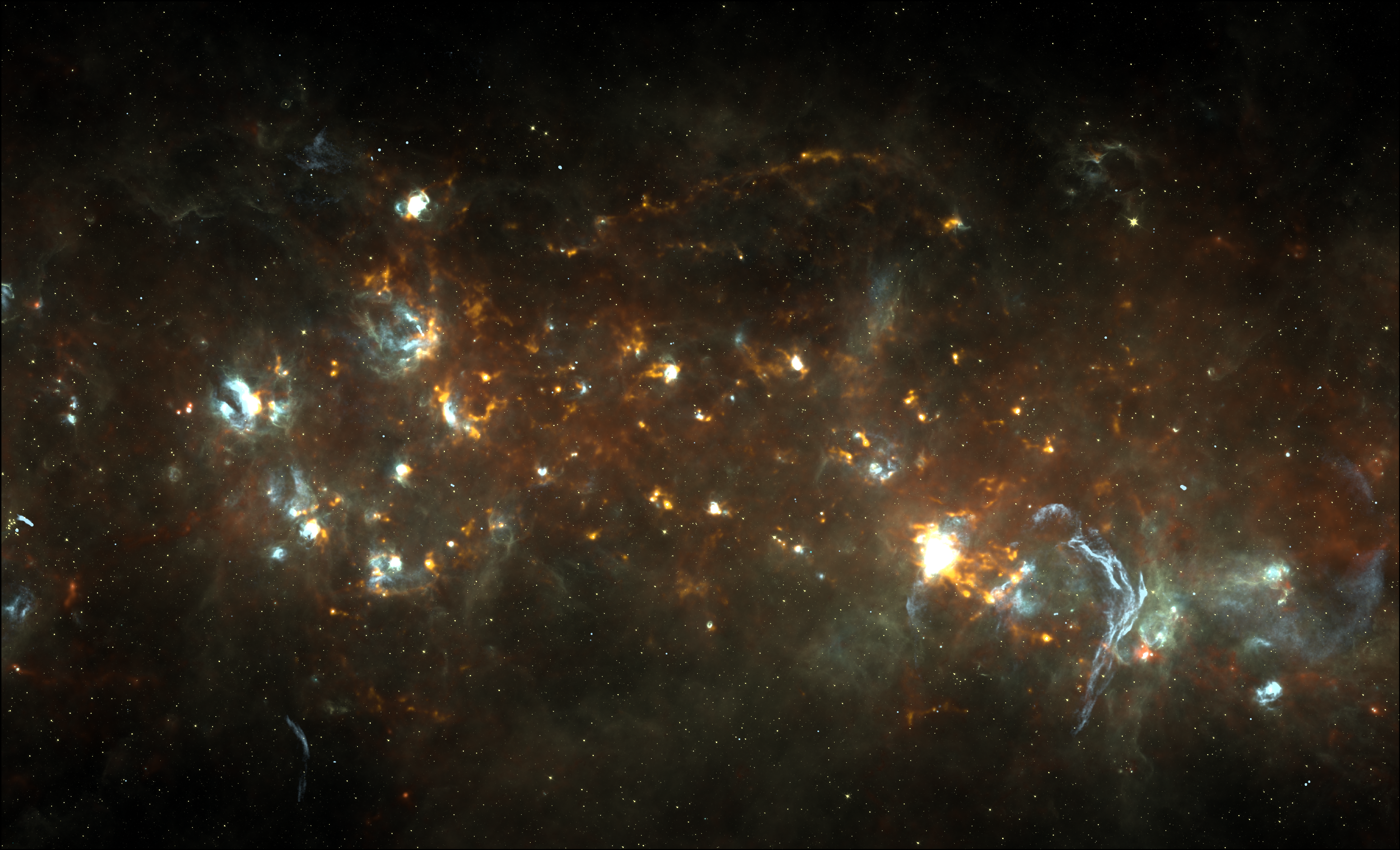

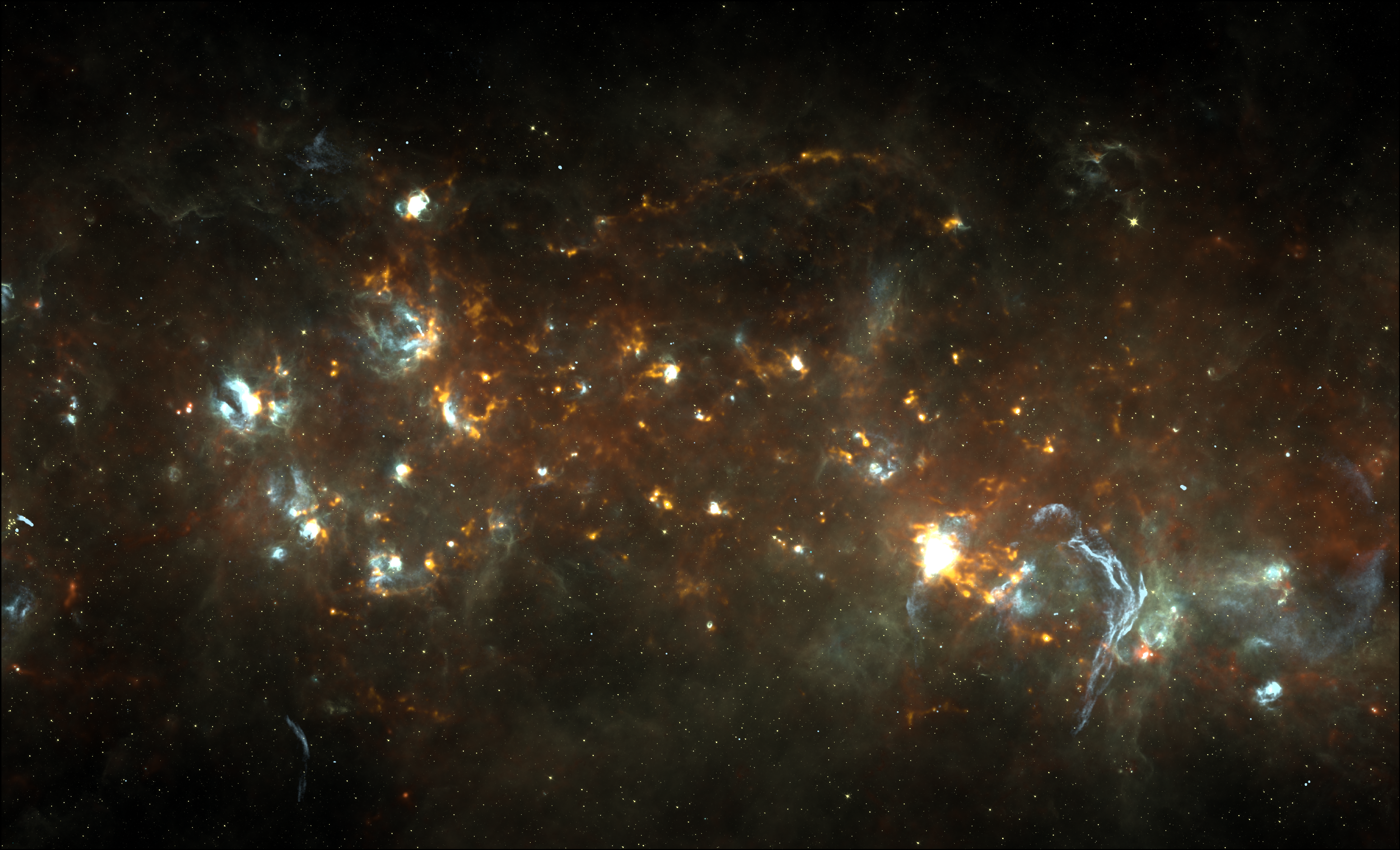

GASTON is a recently-completed 200-hour large programme at the IRAM 30-m telescope, which is using the new NIKA2 camera to conduct various observations of star-forming regions in the Milky Way. One third of the time has been devoted to an extremely deep survey of 2 square degrees of the Galactic plane, which I have been leading since the first observations were made in 2017. In GASTON, we are using the dual-wavelength imaging of NIKA2 at 1 and 2 mm to tackle questions related to star formation and the interstellar medium, and we are using the Galactic plane survey to study the formation of the most massive stars. We have published a paper based on the first results when we had 40% of the data in hand, and have since completed the observations towards. The analysis of the full Galactic plane survey is underway.

The image above is a six-colour composite of the GASTON Galactic plane survey field, centred on a Galactic longitude of 24 degrees, and on the Galactic midplane. The orange colour comes from the GASTON 1 mm imaging, and highlights regions of the densest gas, which may be actively forming star clusters, or in an early stage of star formation before the appearance of any new stars. The blue colours show regions of hot gas, in which bubbles (called HII - "H-two" - regions) are being blown in the interstellar medium by the intense ultraviolet radiation from newly-formed massive stars, or from the expanding shells of supernova remnants.

ALMA & NOEMA: Follow-up studies

I am currently leading observational programmes at the fantastic ALMA (pictured above - image credit: ESO/C. Malin) and NOEMA interferometer facilities.

With NOEMA, we have conducted follow-up observations at 3 mm of a sample of seven infrared-dark clouds (IRDCs), which are excellent targets for studying the very earliest stages of star formation. Such clouds are thought to be at a stage before the growing stellar clusters have managed to significantly heat their surrounding natal clouds, and so are dark at infrared wavelengths. These seven IRDCs are also covered by either the GASTON Galactic plane survey field, or from a pilot study using the NIKA pathfinder instrument which we published in 2018. These data have been combined with observations from the IRAM 30-m telescope to form extremely detailed observations of several key molecules, such as N2H+, HCO+, HCN, and C18O, which will allow us to trace the motion of gas at different densities and very low temperatures.

With ALMA, we are conducting an ambitious programme of follow-up observations of more than 1200 sources identified within GASTON. The observations in the 1 mm band will have much higher resolution than those of GASTON, allowing us to measure the locations and masses of dense gas fragments that give rise to individual star systems that reside within clouds across a wide range of masses. We will use these observations to help us understand where and in what order star clusters are populated with stars of different masses.

CHIMPS & CHIMPS2: The CO Heterodyne Inner Milky Way Plane Survey(s)

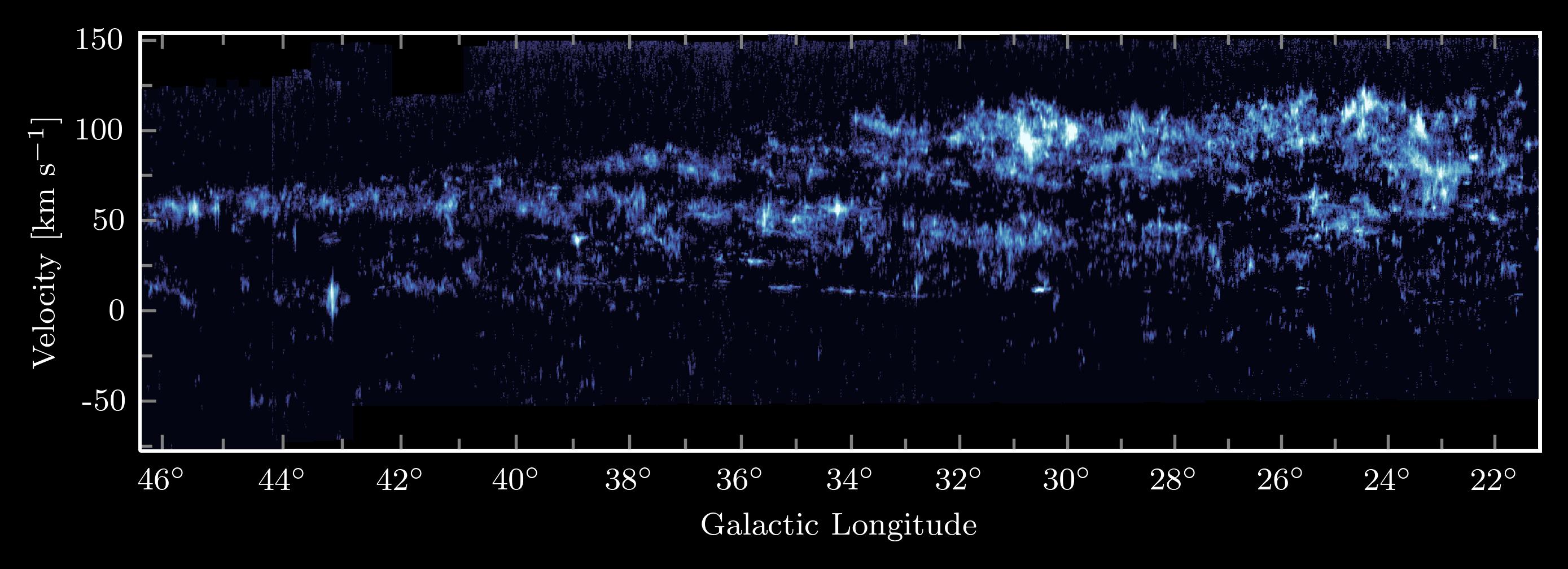

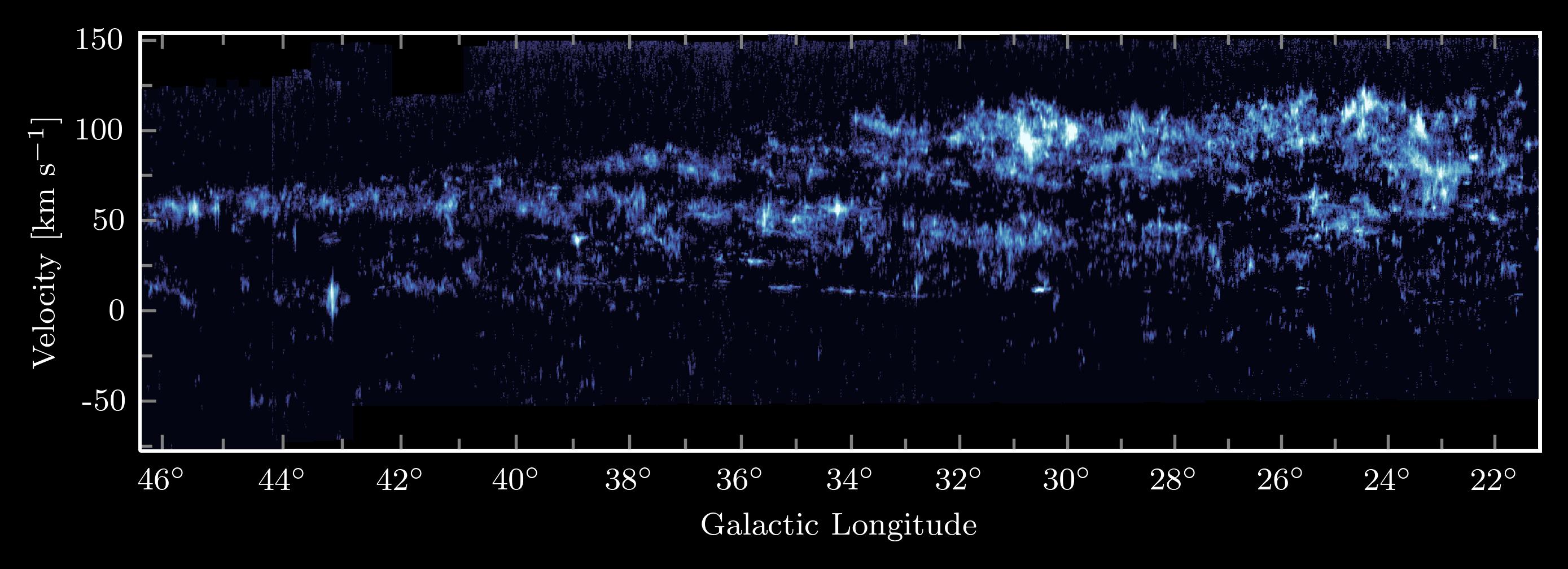

During my PhD I worked on combining a number of observational programmes carried out at the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii into a single coherent data set that became known as CHIMPS. Cold molecular hydrogen makes up the vast majority of the mass of star-forming molecular clouds, but it is effectively invisible at the extremely cold (~10 K) temperatures required for such clouds to form. As the second most abundant molecule in the interstellar medium, carbon monoxide (CO) does emit radiation at these temperatures, and so is one of the best targets for studies of molecular clouds. The CHIMPS observations target rare isotopic forms of CO - 13CO and C18O - in the 3-2 rotational transition, which enable us to see deep into the interiors of clouds of gas where the densities required for star formation are reached.

The CHIMPS observations are particularly great at illustrating the spiral structure of our Galaxy, the evidence of which can be seen in the above position-velocity diagram. The bands of emission sweeping across velocities are the main spiral arms of the Milky Way. The emission of the CO lines happens at a very specific frequency, and so by measuring the change in frequency of the line, we measure the Doppler shift, and thereby determine the velocity of the gas along the line of sight.

With CHIMPS, we were able to study properties of clumps of molecular gas across the spiral arms of the Galaxy, enabling us to examine the effects that the structure of the Galaxy itself has upon star formation. The project was succeeded by CHIMPS2 at the JCMT, with many hundreds of additional hours granted so that we could expand the CHIMPS survey, and extend into the Galatic Centre, and into the Outer Galaxy too.

News

8th Jan 2024

Paper Day!

The dynamic centres of infrared-dark clouds and the formation of cores

by Andrew J. Rigby, Nicolas Peretto, Michael Anderson, Sarah E. Ragan, Felix D. Priestley, Gary A. Fuller, Mark A. Thompson, Alessio Traficante, Elizabeth J. Watkins, Gwenllian M. Williams

Today sees the release, of our new paper, which examines the dense gas at the centres of a sample of infrared-dark clouds using the fabulous NOEMA interferometer (pictured below). NOEMA is an array of twelve (as of 2024) 15-metre antennas, located at an altitude of 2500m on the Plateau de Bure in the French Alps, which observe the same patch of sky simultaneously to reproduce the resolution of a much larger telescope using a technique called interferometry.

This paper is a bit of a landmark for me, as my first foray into interferometry that I have led since its inception. I had a project accepted by the NOEMA time allocation panel back in 2019, which observed a sample of infrared-dark clouds (IRDCs). IRDCs are a sub-class of molecular cloud – clouds of cold and dense molecular hydrogen which are the birth places of stars. As stars begin to form out of the cloud as it collapses under its own gravity, they begin to heat it up, and it then begins to emit strongly at infrared wavelengths. IRDCs are clouds in a very early phase of star formation, before significant heating has begun to occur, and so they are excellent targets to study the conditions that immediately precede star formation.

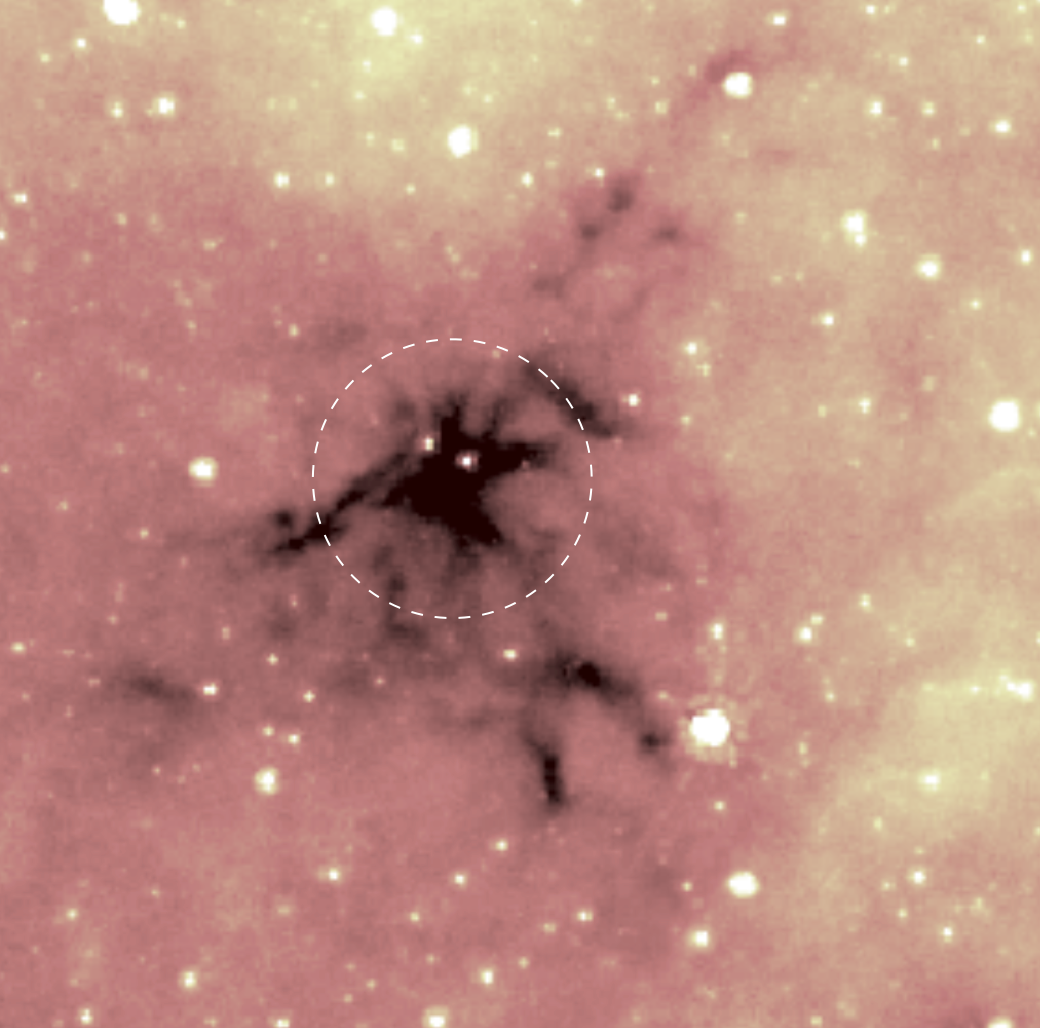

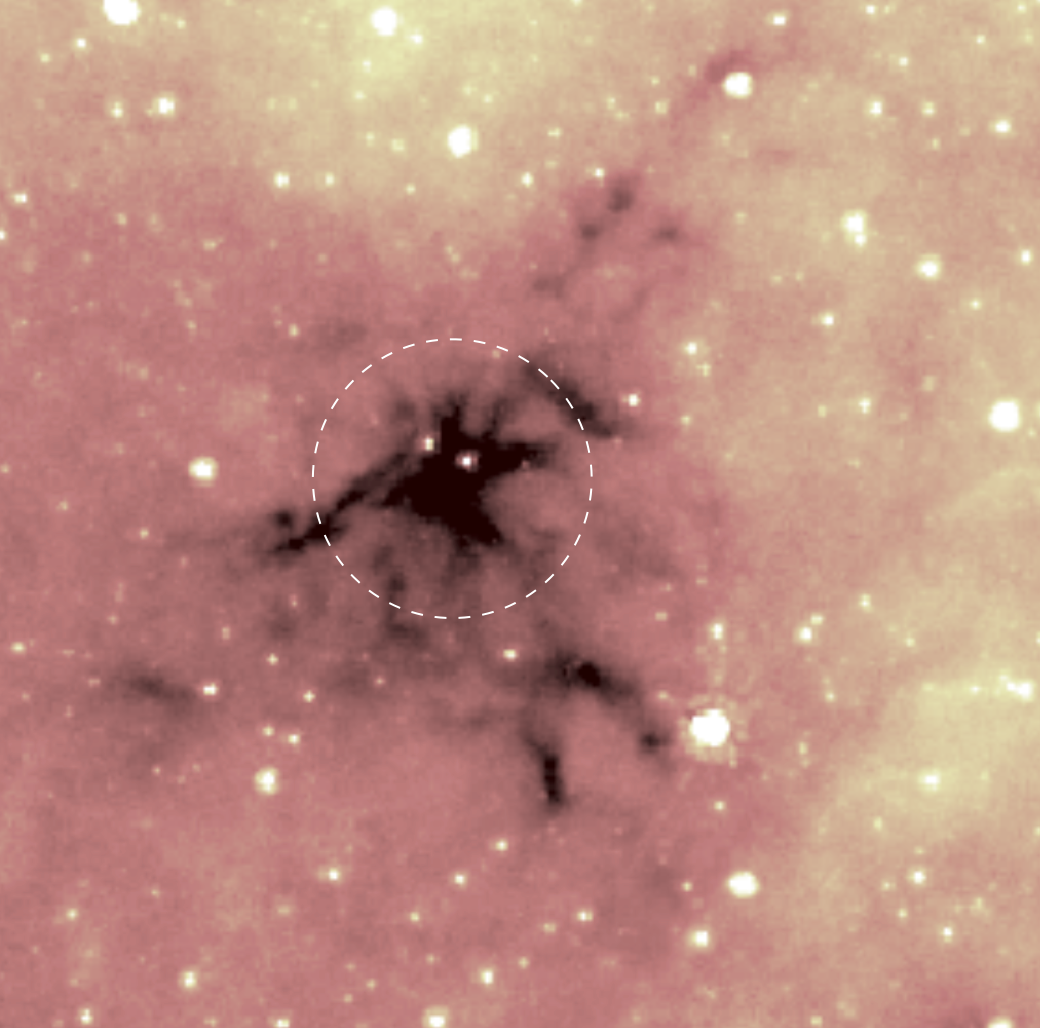

Pictured below is an image from the Spitzer space telescope of an IRDC known as SDC24.489 – one of the targets in our sample. At a wavelength of 8 μm, we can see the cold and dense centre of the cloud as a silhouette against the background. With our NOEMA observations we 'zoomed-in' to the circled region to examine the millimetre-wavelength emission of dust grains and molecules that can give us a handle on what is going on inside.

By examining the motion of dense gas traced by a molecular ion called diazenylium (N2H+) right in the densest centres of these clouds, we found an incredible hive of activity. In all of these clouds, we know that the most massive stars are already being assembled, and it appears that this is happening a highly dynamic and chaotic manner. The level of activity is greatest in the more massive clouds in the sample, although when we study the densest accumulations of gas called 'cores' that are the precursors of star systems, we find that the efficiency with which these clouds assemble cores is pretty universal.

One recent focus of the research efforts of a number of my colleagues across the field, has been on the role of so-called 'hub-filament systems'. SDC24.489 is a good example of a hub-filament system, where the densest part of the cloud is located at the centre of a radial arrangement of filamentary structures. These kinds of systems seem to play a key role in the assembly of the most massive stars – which we usually refer to as stars that are at least eight times as massive as the Sun (which is a fairly petite as stars go) – the ones that explode as supernovae and blow huge bubbles in galaxies with their powerful ultraviolet radiation.

Completely against our expectations, we found a quite clear negative trend between the dominance of the most massive cores and the strength of hub-filament-like cloud shapes. Naively, this would seem to suggest that hub-filament systems are not helping the most massive stars form. However, taken together with other recent results that suggest that all molecular clouds become more hub-filamentary over time as they collapse under gravity (drawing in and focusing nearby filaments), we think we are seeing a hint of how molecular clouds evolve. The most massive cores are the centres of collapse at the earliest times, and they draw in nearby gas within the cloud, fuelling the growth of the core (and the size of the star that will eventually emerge). As time progresses, other cores near the centre of the cloud also begin to swallow up molecular gas and they, in a sense, catch up with the most massive core.

These are early days yet, though, for this kind of study. My good friend Michael Anderson is leading a paper using ALMA observations of a similar sample of IRDCs, which reaches a similar conclusion, and will be out soon. However, we need to return to these kinds of measurements with a vastly expanded sample of clouds to work out whether what we have seen here is a statistical fluke, or if it is indeed representative of the general process. We also need to investigate whether we are misinterpreting the chaotic motions we see in N2H+, which may in fact simply be the result of ordered motions that we have neither the resolution to see, nor the right molecule to probe.

7th December 2021

JCMT Large Progams announced: CLOGS and MAJORS accepted

I'm delighted that the JCMT Time Allocation Committee has approved both of the CLOGS and MAJORS Large Progams, both being led by my good friend David Eden.

CLOGS (the CO Large Outer-Galaxy Survey) builds on the success of CHIMPS2 by significantly expanding the area of the Outer Galaxy survey in the 12CO (3-2) emission line, and will ultimately cover a longitude range of l=198 to 236 degrees. The observations will be used to expand our understanding of the conditions of molecular clouds and star formation in the sparse outer region of the Galaxy, which constitutes a substantially different environment to the comparably well-studied Inner Galaxy.

MAJORS (Massive, Active, JCMT-Observed Regions of Star Formation) will use the ‘Ū’ū instrument to observe a sample of star-forming molecular clouds in the (J=3-2) emission line of the HCN and HCO+ molecules. These molecules are thought to be tracers of the dense gas that is associated with star formation. The goal is to examine the role that dense gas plays in regulating the efficiency of star formation, and enabling a detailed comparison of how these emission lines can be interpreted in studies of other galaxies.

Contact

Dr Andrew J. Rigby

School of Physics and Astronomy

University of Leeds

Leeds

LS2 9JT

United Kingdom

E: a.j.rigby @ leeds.ac.uk

Elements

Text

This is bold and this is strong. This is italic and this is emphasized.

This is superscript text and this is subscript text.

This is underlined and this is code: for (;;) { ... }. Finally, this is a link.

Heading Level 2

Heading Level 3

Heading Level 4

Heading Level 5

Heading Level 6

Blockquote

Fringilla nisl. Donec accumsan interdum nisi, quis tincidunt felis sagittis eget tempus euismod. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus vestibulum. Blandit adipiscing eu felis iaculis volutpat ac adipiscing accumsan faucibus. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus lorem ipsum dolor sit amet nullam adipiscing eu felis.

Preformatted

i = 0;

while (!deck.isInOrder()) {

print 'Iteration ' + i;

deck.shuffle();

i++;

}

print 'It took ' + i + ' iterations to sort the deck.';

Lists

Unordered

- Dolor pulvinar etiam.

- Sagittis adipiscing.

- Felis enim feugiat.

Alternate

- Dolor pulvinar etiam.

- Sagittis adipiscing.

- Felis enim feugiat.

Ordered

- Dolor pulvinar etiam.

- Etiam vel felis viverra.

- Felis enim feugiat.

- Dolor pulvinar etiam.

- Etiam vel felis lorem.

- Felis enim et feugiat.

Icons

Actions

Table

Default

| Name |

Description |

Price |

| Item One |

Ante turpis integer aliquet porttitor. |

29.99 |

| Item Two |

Vis ac commodo adipiscing arcu aliquet. |

19.99 |

| Item Three |

Morbi faucibus arcu accumsan lorem. |

29.99 |

| Item Four |

Vitae integer tempus condimentum. |

19.99 |

| Item Five |

Ante turpis integer aliquet porttitor. |

29.99 |

|

100.00 |

Alternate

| Name |

Description |

Price |

| Item One |

Ante turpis integer aliquet porttitor. |

29.99 |

| Item Two |

Vis ac commodo adipiscing arcu aliquet. |

19.99 |

| Item Three |

Morbi faucibus arcu accumsan lorem. |

29.99 |

| Item Four |

Vitae integer tempus condimentum. |

19.99 |

| Item Five |

Ante turpis integer aliquet porttitor. |

29.99 |

|

100.00 |